A first success and a final gem

Sinfonieorchester Basel

3 and 4 April 2019

Antoine Tamestit, viola

Marek Janowski, conductor

Béla Bartók - Concerto for viola and orchestra

Anton Bruckner - Symphony No. 7

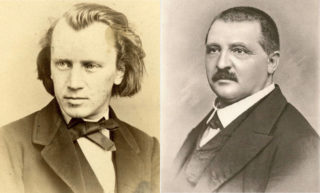

The 60-year-old Anton Bruckner must have been elated after the performance of his seventh symphony on the 10th of March 1885 in Munich. For the first time in his life, his work was met with undiluted enthusiasm. Prominent people from the Bavarian capitol’s artistic elite wanted to meet him, there was a photoshoot and his portrait was even painted. The conductor praised the symphony as the best one since Beethoven, whose shadow was looming large over many 19th-century composers.

Admittedly, as a devoted Wagner admirer, Bruckner may have had a leg up with the audience in Munich, a Wagner “Hochburg” (stronghold) at the time. The composer himself confirmed the rumor that the Adagio was partly written as funeral music for the great master, who died around the time Bruckner was composing his seventh symphony. There are several similarities between Bruckner’s Adagio and Siegfried’s funeral march by Wagner. Not only do the pieces have similar solemn tempos, but the structure and the instrumentation have remarkable resemblances too, e.g. the use of tubas and horns.

Just as in previous symphonies, Bruckner used strongly contrasting themes as building blocks, but they blend into each other more seamlessly. The themes also stick easier, making the symphony as a whole more digestible and easier to remember when heard for the first time.

Just like Bruckner (1824-1896), Bartók (1881-1945) was born and raised in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but although their lives overlapped by fifteen years, there are striking differences between Bruckner and Bartók, whose viola concerto is on this month’s program. While Bruckner was a deeply religious, largely self-taught admirer of Wagner, the atheist Bartók received formal education at the Budapest conservatory where he fell under the spell of Brahms.

Bartók’s viola concerto, his last work, was unfinished when he died from leukemia in 1945 in New York. His student and friend Tibor Serly took it upon himself to complete the score and the concerto was eventually premiered in 1949 by the Minnesota Symphony Orchestra under Antal Dorati, who himself had been a student of Bartók. Bartók’s son Peter decided in the 1990s to make a fresh attempt at finalizing the unfinished score. It is this version the French violist Antoine Tamestit will play. As Tamestit says (interview in German, p. xx), he believes Peter Bartók’s version lies closer to the original score. Over the last six years the violist has been working from this version and the original one, thus developing a deep understanding of the possible intentions of the composer allowing him to add his own bow strokes and articulation. The concerto’s first movement is characterized by the use of a modern tonal language, typical for Bartók later works and, as Tamestit explains, reminiscences of folk music are present throughout the entire three-movement piece. He considers it his biggest challenge to make the piece understandable for the audience right from the first bars. So, prick up your ears and let the eminent violist uncover the secrets of this gem of the viola repertoire.

These English program notes have been published in the magazine (No. 7, 2018/2019) of the Sinfonieorchester Basel.

Comments