A Provocative Pairing

Sinfonieorchester Basel

3 and 4 February 2021

Ivor Bolton, Conductor

Sol Gabetta, Violoncello

(Original program - Concert was canceled due to Covid-19 restrictions)

Camille Saint-Saëns - Le Rouet d'Omphale, op.31

Helena Winkelman - Goblins

Camille Saint-Saëns - Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra, No.2

Camille Saint-Saëns - Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra, No.1

Domenico Melchiorre - Sphaira

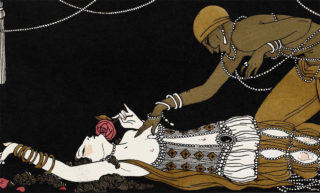

Camille Saint-Saëns - Bacchanale from Samson et Dalila

This month’s concert is not only a celebration of the Stadtcasino’s reopening, it is also a commemoration of one of France’s greatest composers, Camille Saint-Saëns, who passed away one hundred years ago. Unrelated events? Perhaps, but brought together ingeniously.

For the reopening, SOB commissioned several new compositions. Besides a second new work by Basel-based Helena Winkelman – the first was performed in September –, this month’s concert also features the premiere of Sphaira, a piece by fellow Basler Domenico Melchiorre. Using innovative percussion of his own making, we hear how after a long standstill, the cosmic movements of the planets resume, thus drawing a parallel with the prolonged closure of the Stadtcasino. Melchiorre borrowed the idea of attributing sound to the movement of the planets from Pythagoras.

With four works, the main part of the concert is dedicated to Saint-Saëns.

Born in 1835 and having died in 1921, the size of his oeuvre is reflected in his long and prolific life. There are 169 works with an opus number (and many without), including five symphonies, five piano concertos, thirteen operas, four symphonic poems (e.g. Le Rouet d’Omphale), dozens of songs, and a host of chamber music pieces. Who can’t see in the mind’s eye the swan from Le Carnaval des Animaux elegantly sailing the waters, or hear the rattling bones of the dancing skeletons in the Dance Macabre? His first Cello Concerto, one of the very few able to stand up against the force of an orchestra, is a favorite of many cellists.

By many accounts Saint-Saëns’ life was hugely successful. A child prodigy, he played his first concert at the age of eleven. (Some consider his precocious talents more striking than Mozart’s.) He was a member of the prestigious Institut de France and Liszt called him the greatest organist in the world. (For twenty years Saint-Saëns was the organist of La Madeleine, the French imperial church). Most importantly, his compositions and his work as a conductor and soloist were met with appreciation, not only in France, but also abroad, and he ultimately received a state funeral.

Nonetheless, his life wasn’t without its dark pages. His father died when he was just a few weeks old, and both his sons died in infancy after which his marriage quickly deteriorated and ended in separation. (His presumed homosexuality may have played a role too.)

There were also setbacks in his professional life, for example the lack of interest for his masterpiece, the opera Samson et Dalila. Its premiere eventually took place in Germany under the baton of Liszt. As flattering as Liszt was, his countryman Berlioz ambiguously said: “He knows everything, but lacks inexperience.”

However, most telling was his work’s gradual loss of relevance. While Saint-Saëns was an advocate of modern German composers such as Wagner in his early years, later in life he turned more nationalistic in his taste and was unwilling to absorb new trends of which Debussy and Schönberg were the most prominent exponents. It is all the more provocative that SOB is pairing his compositions in this celebratory and commemorative year with some brand-new modern works.

These English program notes have been published in the magazine of the Sinfonieorchester Basel.

Main photo of Domenico Melchiorre by Hannes Bärtschi.

Comments